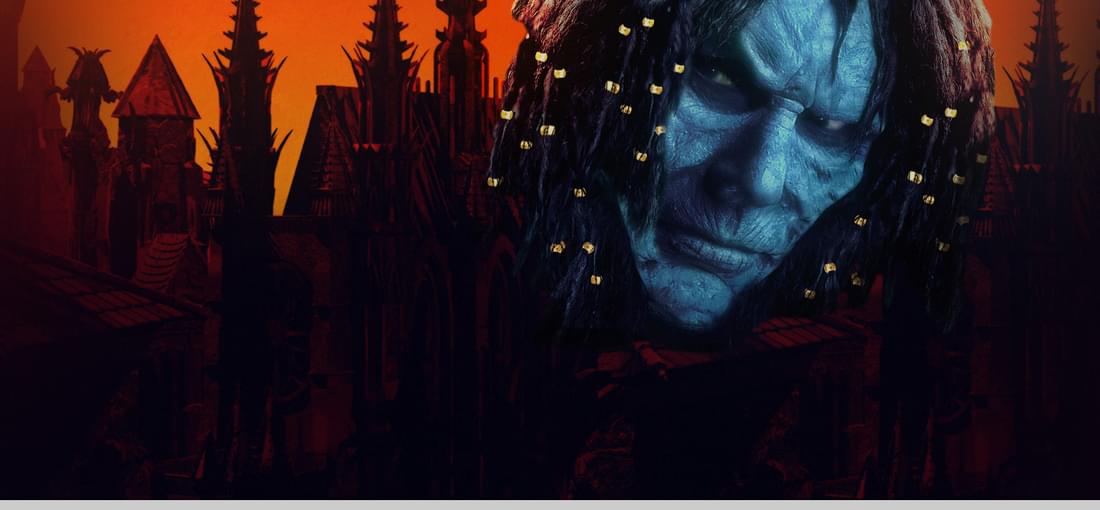

PlaneScape: Torment is an amazing game if you're the sort that enjoys plot and character development over game mechanics. In fact, this game reminds me much of The Longest Journey in that the gameplay elements play second fiddle, and much of the journey you embark on is ultimately about self-discovery more than becoming some epic savior. It may play long for people who don't have a lot of patience and don't enjoy reading (as is mentioned from other sources, the script was over 5,000 pages long and somewhere around 800,000 words). There's just an amazing amount of detail and work put into this game in terms of fleshing out the environments, its inhabitants, and the player characters. If you enjoy flawed masterpieces such as Fallout, The Longest Journey, Arcanum, and the like, then this should be a no brainer.

I remember first playing this game when I was still in elementary school. It was my first Tex Murphy game (the friend who introduced me to it mentioned others, such as Martian Memorandum; he also introduced me to the likes of 7th Guest, Phantasmagoria, and King's Quest VI). Even as a young kid, I found this game extremely enthralling and charming. It's still a pretty singular experience, even if it's dated, and I've been trying to find a copy ever since I sold my old one back during middle school. If you haven't played this game, but you wouldn't mind enjoying an adventure game with off-color humor and a bit of pulp parody, give this one a whirl.

Fallout, while like much of the future work of the minds behind it (i.e. inventive, but somewhat poorly constructed), stands as a paragon of what a CRPG should strive to be. The game was thematically strong, and despite some intentionally caricatured elements, it brought about a sense of verisimilitude in the way its populations and communities were portrayed. While the dialogue could be a little awkward at points, for the most part, it felt mundane and reasonable. Also, the violence didn't exist in its quantities or qualities to be shocking or comedic, but rather it existed to be excessive and gritty, and make it feel commonplace and cheap, as reflective of the attitudes and conditions of such an unregulated world. And the last words are on some of the game's fundamental mechanics - specifically, the way Fallout handled statistics, leveling, and morality. The subject is closely tied to the success of Fallout's other elements, as these mechanics can affect the tone and tempo of the game, and fall out of sync with it as well. Perhaps the greatest part was the elimination of grinding as a primary or even reasonable method of character advancement - most experience could be gleaned simply by playing your character through the course of the game. This allowed a much wider set of options for viable styles of play. Without having to grind for experience, combat-oriented characters, while still effective in their own way, were not the only characters that could be reasonably effective. As for the way Fallout handled morality, I found this feature to be pivotal to the experience (perhaps that's the existentialist in me). Perhaps another way to phrase my point is the way that Fallout lacked the handling of morality. There was no dualistic morality system (e.g. Fable, Oblivion, Knights of the Old Republic, Mass Effect, etc.), there were simply actions and the resulting consequences (which were at some points a little buggy). I believe this opens up - again - more varied styles of play without the game shoehorning the player into a role by a series of arbitrary moral value judgments. I just don't believe dualistic morality systems work well in many games, simply because they either push a player down a path and restrict him or her, or in trying to offer concessions for a more open style of play, they ultimately render their own morality system next to useless (Fallout 3, I'm looking at you as the most recent example).